A herniation, fundamentally, is the abnormal displacement of tissue through a weakened area of an anatomical structure, manifesting commonly in spinal conditions such as lumbar and cervical disc herniations. This phenomenon can be attributed to a variety of factors, including mechanical stress, genetic predispositions, and biochemical imbalances that compromise the integrity of structures like the annulus fibrosus. The resultant symptoms, which may include radicular pain, sensory disturbances, and motor deficits, highlight the complexity of this condition. Exploring the nuances of herniation types and their specific therapeutic requirements reveals much about their management and prevention strategies.

Definition of Herniation

A herniation refers to the abnormal protrusion of an organ or tissue through a defect or weakened area in the surrounding anatomical structure, often leading to compromised function and potential clinical complications. This phenomenon can occur in various anatomical regions and involves different types of tissues, with each type presenting unique clinical challenges. Among the most common manifestations is inguinal herniation, which involves the protrusion of abdominal contents through the inguinal canal, a structure located in the lower anterior abdominal wall.

Inguinal herniation typically results from a combination of increased intra-abdominal pressure and weaknesses in the abdominal wall, often exacerbated by factors such as heavy lifting, chronic coughing, or congenital defects. Clinically, patients may present with a palpable bulge in the groin region, discomfort, and, in advanced cases, obstruction or strangulation of the herniated tissue, necessitating prompt medical attention.

Surgical intervention remains the definitive treatment modality for inguinal herniation, aiming to reduce the herniated tissue back into the abdominal cavity and reinforce the weakened area with techniques such as mesh repair. The choice of surgical approach—open or laparoscopic—depends on patient-specific factors and surgeon expertise, with each method having distinct advantages and potential complications.

Common Types

Herniation mainly occurs in the intervertebral discs, with lumbar disc herniation and cervical disc herniation being the most prevalent types. Lumbar disc herniation typically affects the lower back, often resulting in radiculopathy or sciatica due to nerve root compression. Cervical disc herniation, on the other hand, impacts the neck region and can cause symptoms such as neck pain, arm pain, and numbness or weakness in the upper extremities.

Lumbar Disc Herniation

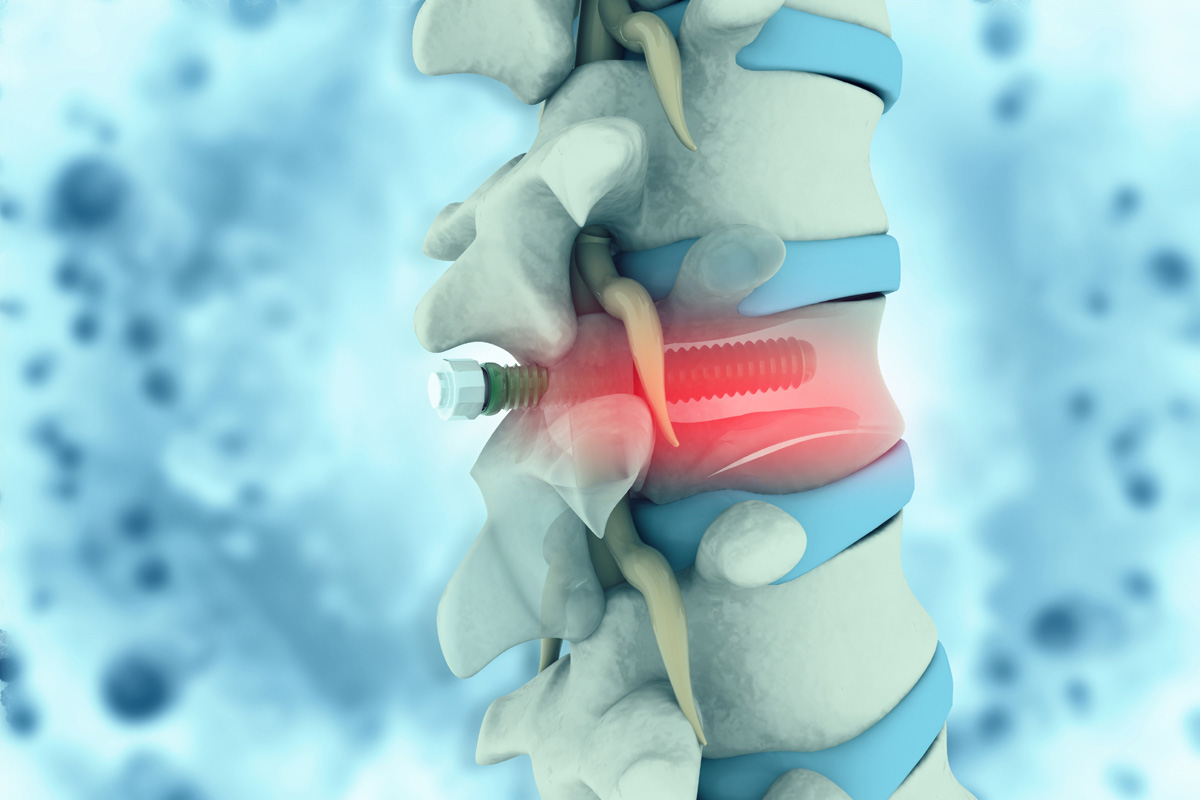

Lumbar disc herniation, frequently classified by its anatomical position and severity, encompasses several common types such as protrusion, extrusion, and sequestration. Protrusion, the least severe form, involves the nucleus pulposus bulging outward but remaining contained by the annulus fibrosus. This type often responds well to conservative treatments, including physical therapy designed to strengthen the surrounding musculature and alleviate pressure on the affected nerve roots.

Extrusion occurs when the nucleus pulposus extends through the annulus fibrosus but remains connected to the disc. This condition may necessitate more aggressive treatment modalities, potentially including surgical intervention if conservative measures prove insufficient. The presence of significant neurological deficits, such as motor weakness or severe radiculopathy, often guides the decision towards surgical decompression.

Sequestration represents the most severe form of lumbar disc herniation, characterized by the nucleus pulposus fragmenting and migrating away from the disc space. This can lead to substantial neural compression and demands prompt medical attention. Surgical intervention is frequently required to remove the extruded material and decompress the affected neural elements. Post-surgical rehabilitation, including physical therapy, is important to restore functional mobility and prevent recurrence. Each type of lumbar disc herniation necessitates a tailored therapeutic approach to optimize patient outcomes.

Cervical Disc Herniation

Cervical disc herniation, often manifesting with symptoms such as neck pain, radiculopathy, and potential neurological deficits, is typically categorized into types like protrusion, extrusion, and sequestration based on the extent and nature of disc displacement. Protrusion involves the nucleus pulposus pressing against the annulus fibrosus without breaching it. Extrusion occurs when the nucleus pulposus breaks through the annulus fibrosus but remains connected to the disc. Sequestration represents the most severe form, where a fragment of the nucleus pulposus separates entirely from the disc, potentially migrating within the spinal canal.

Clinical management of cervical disc herniation often begins with conservative treatments, including physical therapy, which focuses on exercises to strengthen neck muscles, improve range of motion, and alleviate pain. When conservative measures fail, surgical options may be considered. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) and cervical disc arthroplasty are two prevalent surgical interventions. ACDF involves the removal of the herniated disc and fusion of the adjacent vertebrae, while cervical disc arthroplasty aims to replace the damaged disc with an artificial one, preserving motion at the affected spinal level. Both approaches aim to relieve neural compression and restore spinal stability, tailored to the patient’s specific pathology and clinical presentation.

Causes

The etiology of herniation is multifactorial, often arising from a combination of mechanical, genetic, and biochemical factors that contribute to the weakening of the annulus fibrosus. Lifestyle factors, such as smoking and obesity, play a significant role in accelerating disc degeneration. Smoking impairs the microcirculation within the intervertebral discs, reducing nutrient supply and leading to decreased disc resilience. Obesity increases mechanical stress on the spinal column, exacerbating wear and tear on the annulus fibrosus.

Occupational hazards also contribute substantially to the risk of herniation. Jobs that require repetitive lifting, prolonged sitting, or frequent bending and twisting can lead to cumulative trauma on the spinal discs. For instance, heavy manual laborers and long-haul truck drivers are at a heightened risk due to constant mechanical stress and vibration exposure, respectively. Additionally, genetic predisposition can influence disc structure integrity, rendering some individuals more susceptible to herniation.

Biochemical factors, including age-related changes in the composition of the nucleus pulposus, further exacerbate the weakening of the annulus fibrosus. Proteoglycan loss and decreased water content in the nucleus pulposus diminish its ability to absorb shock, increasing the likelihood of annular tears and subsequent herniation.

Symptoms

Patients with herniation commonly present with radicular pain, which radiates along the path of the affected nerve root. This symptom is often indicative of nerve compression, where the herniated material exerts pressure on the adjacent nerve structures. The intensity of pain can vary greatly, ranging from mild discomfort to severe, incapacitating pain. The specific distribution of pain depends on the anatomical location of the herniation, with cervical herniations typically affecting the upper extremities and lumbar herniations impacting the lower extremities.

In addition to radicular pain, patients may experience localized pain at the site of herniation. This localized pain is often described as a deep, aching sensation and can be exacerbated by movements that increase intra-abdominal pressure, such as coughing or sneezing. Neurological deficits are another critical symptom, including sensory disturbances like numbness, tingling, or a burning sensation, and motor deficits manifesting as muscle weakness or atrophy in the affected limb.

Reflex changes can also occur, with diminished or absent reflexes in the distribution of the affected nerve root. These symptoms are critical in the clinical evaluation, guiding diagnostic imaging and subsequent therapeutic interventions. The correlation between symptomatology and imaging findings is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective management.

Herniated Disc

Herniated discs, a common cause of radicular pain and neurological deficits, occur when the nucleus pulposus protrudes through the annulus fibrosus, leading to nerve root compression and inflammation. This pathological condition most frequently affects the lumbar and cervical regions of the spine, presenting with symptoms such as sciatica, motor weakness, and sensory disturbances. Diagnostic modalities often include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans, which confirm the extent of disc herniation and nerve involvement.

Non-surgical therapies are the cornerstone of initial management for herniated discs. These may include pharmacological interventions such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, and muscle relaxants. Physical therapy plays a crucial role, incorporating exercises designed to strengthen the paraspinal muscles and improve spinal alignment. Epidural steroid injections may also be utilized to reduce inflammation and provide temporary pain relief.

Lifestyle modifications are essential for long-term management and prevention of recurrent disc herniation. Patients are advised to maintain a healthy weight, engage in regular low-impact aerobic exercises, and adopt ergonomic practices both at work and home. Smoking cessation is strongly recommended, as smoking impairs disc nutrition and accelerates degenerative changes. Through these measures, many patients achieve significant symptomatic relief and functional improvement without the need for surgical intervention.

Brain Herniation

Brain herniation, a critical neurological condition, occurs when intracranial pressure causes brain tissue to shift abnormally within the skull. This can manifest in various types, including subfalcine, transtentorial, and tonsillar herniations, each with distinct pathophysiological characteristics. Identifying the underlying causes, such as traumatic brain injury or intracranial hemorrhage, alongside prompt diagnostic imaging and emergent intervention, is crucial for excellent patient outcomes.

Types of Herniations

When intracranial pressure increases, it can lead to brain herniation, a critical condition where brain tissue is displaced due to swelling or mass effect, resulting in potentially life-threatening consequences. Unlike inguinal herniation, which involves the protrusion of abdominal content through the inguinal canal, or femoral herniation, which occurs through the femoral canal, brain herniation involves the displacement of intracranial structures.

There are several types of brain herniations, classified by their anatomical locations and the direction of tissue displacement. Subfalcine herniation, the most common type, involves the cingulate gyrus being pushed under the falx cerebri. Transtentorial herniation can be further subdivided into uncal and central herniations. Uncal herniation involves the uncus of the temporal lobe herniating over the tentorial notch, often compressing the midbrain. Central herniation involves downward displacement of the brainstem. Tonsillar herniation, or cerebellar herniation, occurs when the cerebellar tonsils are forced through the foramen magnum, risking compression of the medulla oblongata, essential for autonomic functions. Each type of brain herniation requires prompt diagnosis and intervention due to the severe and potentially fatal outcomes associated with intracranial pressure dynamics.

Causes and Symptoms

Intracranial herniation can result from various etiologies, including traumatic brain injury, intracranial hemorrhage, brain tumors, or ischemic stroke, each contributing to abnormal intracranial pressure dynamics and subsequent tissue displacement. Elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) can force brain tissue to move from its normal position, leading to potentially fatal outcomes if not promptly managed.

Clinically, brain herniation presents with a spectrum of symptoms contingent on the herniation type and affected brain regions. Common manifestations include altered consciousness, anisocoria (unequal pupil size), hemiparesis, and decerebrate or decorticate posturing. Further, patients may exhibit Cushing’s triad—hypertension, bradycardia, and irregular respiration—indicative of severe ICP elevation.

Preventative strategies, although not always applicable post-diagnosis, can involve lifestyle changes and ergonomic adjustments aimed at mitigating risks associated with brain injury. For instance, adopting safe practices to prevent head trauma and managing comorbid conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes, can play a significant role. Ergonomic adjustments in daily activities, including proper headgear usage and fall prevention measures, can also reduce the incidence of traumatic brain injuries, thereby lowering the risk of herniation.

Understanding the nuanced causes and symptoms of brain herniation is pivotal for timely diagnosis and intervention, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Diagnostic and Treatment

Thorough diagnosis of brain herniation necessitates a complete neurological examination coupled with advanced imaging modalities, such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), to identify the extent and location of herniation. The physical examination is pivotal for detecting clinical signs such as altered consciousness, pupil dilation, and motor deficits, which can indicate increased intracranial pressure and impending herniation. CT scans offer rapid, detailed imaging of bony structures and hemorrhages, while MRI provides superior soft tissue contrast, allowing for better delineation of brain structures and identification of herniation types.

Upon confirmation of brain herniation, immediate treatment is vital to mitigate neurological damage. Initial management often includes measures to lower intracranial pressure, such as osmotic diuretics, hyperventilation, and corticosteroids. However, definitive treatment frequently requires surgical intervention. Decompressive craniectomy, a procedure where a portion of the skull is removed to allow the swollen brain to expand without being compressed, is a common surgical approach. Other interventions might include the evacuation of hematomas or cerebrospinal fluid drainage via ventriculostomy. Successful outcomes hinge on prompt diagnosis and timely, appropriate therapeutic strategies, underscoring the importance of rapid clinical and imaging assessments.

Abdominal Herniation

An abdominal herniation occurs when an organ or tissue protrudes through a weakened spot in the abdominal wall, often resulting in a noticeable bulge and potential complications if left untreated. This condition is classified based on the anatomical location and the specific structures involved. Two prevalent types are inguinal herniation and umbilical herniation.

Inguinal herniation, the most frequently encountered form, occurs when part of the intestine or fatty tissue pushes through the inguinal canal in the lower abdomen. This type mainly affects males due to the natural weakness in the groin area where the spermatic cord passes. Clinically, patients may present with a visible or palpable bulge in the groin, which may increase in size upon straining. Symptoms can include pain, discomfort, and sometimes complications such as incarceration or strangulation, necessitating prompt surgical intervention.

Umbilical herniation, on the other hand, involves the protrusion of intra-abdominal contents through an opening in the umbilicus (navel). This type is frequently observed in infants due to incomplete closure of the abdominal wall post-birth, though it can also affect adults. Clinical manifestations include a soft bulge at the umbilicus, which may become more pronounced with activities like coughing or lifting heavy objects. While many cases in infants resolve spontaneously, surgical repair may be indicated in persistent or symptomatic cases.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of herniation necessitates a multifaceted approach encompassing advanced imaging techniques such as MRI and CT scans, which provide high-resolution images for accurate assessment. Common diagnostic tests, including ultrasound and physical examinations, play an essential role in identifying the presence and extent of hernias. Clinicians must also evaluate symptoms and clinical indicators, such as localized pain and visible bulging, to formulate a thorough diagnostic overview.

Imaging Techniques Used

Diagnostic imaging techniques are essential for accurately identifying the presence and extent of herniation. Among these techniques, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is often considered the gold standard due to its superior soft-tissue contrast resolution. MRI protocols for herniation typically involve T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and fat-suppressed sequences to better visualize the herniated tissue against adjacent anatomical structures. These protocols are meticulously designed to capture high-resolution images that can discern the degree of disc protrusion, nerve root impingement, and any accompanying inflammatory changes.

Computed Tomography (CT) scans are another pivotal imaging modality, particularly useful for evaluating bony structures and calcified disc herniations. CT imaging provides axial, sagittal, and coronal reconstructions, which are invaluable for evaluating the spatial relationships between vertebrae and the herniated disc material. The high spatial resolution of CT scans can also detect subtle osseous abnormalities that might contribute to or result from herniation.

Both MRI and CT scans offer complementary insights, with MRI excelling in soft tissue evaluation and CT scans providing detailed bony anatomy. The choice of imaging technique is often dictated by the clinical scenario, patient condition, and specific diagnostic requirements, ensuring a thorough evaluation of herniation.

Common Diagnostic Tests

Regularly, the diagnosis of herniation involves a thorough combination of physical examinations and specialized diagnostic tests to accurately assess the severity and impact on the patient. Physical examinations typically include a neurological assessment to evaluate motor function, sensory response, and reflex integrity.

Among the specialized diagnostic tests, Myelogram analysis plays a pivotal role. This imaging technique involves injecting a contrast dye into the spinal canal, followed by X-ray or CT scans to visualize the spinal cord and nerve roots. Myelograms are particularly useful for identifying compressions or distortions caused by herniated discs.

In addition to imaging, Electrodiagnostic testing, such as electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies (NCS), provides valuable insights. EMG measures the electrical activity of muscles at rest and during contraction, helping to pinpoint muscle weakness or denervation. NCS evaluates the speed and strength of electrical signals traveling through peripheral nerves. These tests are instrumental in diagnosing nerve damage and differentiating between herniation and other neuromuscular disorders.

Combining these diagnostic approaches allows for a thorough evaluation, ensuring that clinicians can devise a targeted and effective treatment plan tailored to the specific needs of the patient.

Symptoms and Indicators

Identifying a herniation often begins with recognizing its hallmark symptoms, such as localized pain, radiating pain, numbness, and muscle weakness, which can provide critical initial clues for clinicians. Localized pain typically manifests near the site of the herniation, whereas radiating pain may traverse along the pathway of the affected nerve, often impacting the extremities. This radicular pain, frequently described as sharp or burning, can severely impair daily activities. Numbness and paresthesia in the associated dermatome, along with muscle weakness, may indicate nerve compression, necessitating prompt clinical evaluation.

A thorough patient history and physical examination are essential for accurately diagnosing herniation. Clinicians may employ specific maneuvers to reproduce symptoms and pinpoint the affected nerve root. For instance, the Straight Leg Raise test can help confirm lumbar disc herniation. Diagnostic imaging, such as MRI or CT scans, further substantiates the clinical findings by visualizing the herniated disc and its impact on adjacent neural structures.

Effective pain management strategies, including pharmacological interventions and physical therapy, are vital for alleviating symptoms. Additionally, lifestyle modifications, such as ergonomic adjustments and weight management, play a pivotal role in preventing exacerbation and promoting long-term spinal health. Early diagnosis and tailored treatment plans greatly improve patient outcomes in herniation cases.

Treatment Options

Treatment options for herniation vary based on the severity of the condition, ranging from conservative management techniques to surgical interventions. Initial management often includes physical therapy, which focuses on strengthening the muscles surrounding the herniated area, improving flexibility, and reducing pain through targeted exercises and manual therapy. Techniques such as McKenzie exercises and core stabilization routines are frequently utilized to alleviate pressure on the affected nerves and discs.

Pharmacological approaches may involve nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, or muscle relaxants to mitigate inflammation and discomfort. In cases where conservative methods fail to yield satisfactory relief, more invasive procedures may be considered.

Epidural steroid injections can provide temporary pain relief by delivering anti-inflammatory medication directly to the affected region. When these measures prove inadequate, surgical intervention becomes a viable option. Procedures such as microdiscectomy or laminectomy aim to remove or repair the herniated disc material, thereby decompressing the affected neural structures. Advanced techniques like minimally invasive spine surgery (MISS) offer the benefits of reduced recovery times and lower complication rates compared to traditional open surgery.

Ultimately, the choice of treatment is tailored to the individual patient’s clinical presentation, severity of symptoms, and overall health status.

Prevention

Implementing preventive strategies is essential in reducing the risk of herniation and promoting long-term spinal health. One of the primary measures involves adopting ergonomic practices, particularly in occupational settings where prolonged sitting or repetitive lifting is common. Ergonomic interventions include adjusting chair height, using lumbar support, and ensuring that workstations are at eye level to prevent undue strain on the spine. Additionally, proper lifting techniques, such as bending at the knees and keeping heavy objects close to the body, are vital in mitigating the risk of disc herniation.

Core strengthening exercises are equally vital in prevention. A robust core stabilizes the spine, distributing mechanical loads more evenly and reducing the likelihood of disc protrusion. Specific exercises, such as planks, bridges, and abdominal crunches, target the muscles surrounding the spine, enhancing their ability to support spinal structures under various stresses. Engaging in regular physical activity not only fortifies core muscles but also improves overall flexibility and posture, further diminishing herniation risks.

When to Seek Help

Recognizing the appropriate time to seek medical intervention for herniation is vital to prevent potential complications and guarantee effective treatment. Herniations, depending on their location and severity, can lead to significant morbidity if not addressed promptly. Emergency situations warranting immediate attention include cauda equina syndrome, characterized by severe lower back pain, loss of bowel or bladder control, and significant motor weakness. This condition necessitates urgent surgical evaluation to prevent irreversible neurological damage.

In non-emergent scenarios, a medical consultation is advised when symptoms such as persistent pain, numbness, or tingling that radiate along the affected nerve path are observed. These symptoms may suggest nerve compression, necessitating diagnostic imaging such as MRI or CT scans to ascertain the extent of herniation. Additionally, progressive weakness or atrophy in the affected musculature is an indicator for prompt medical evaluation.

Chronic symptoms unresponsive to conservative management, including physical therapy, analgesics, or lifestyle modifications, also necessitate medical consultation. In such cases, a specialist may consider interventional procedures like epidural steroid injections or surgical options. Timely intervention is crucial in mitigating long-term sequelae and enhancing patient outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Herniation Occur Due to Genetic Factors?

Herniation can indeed result from genetic predispositions. Specific genetic factors may influence the structural integrity of connective tissues, leading to herniation inheritance patterns within families, thereby increasing the likelihood of herniation occurrences.

Are There Any Specific Exercises to Prevent Herniation?

To prevent herniation, specific exercises focus on posture correction and core strengthening. These exercises enhance spinal stability and reduce strain, including planks, bridges, and pelvic tilts, which help maintain proper alignment and support spinal health.

How Does Diet Influence the Risk of Herniation?

Diet influences the risk of herniation by contributing to nutrient deficiencies and promoting inflammatory responses. Inadequate intake of essential nutrients weakens spinal structures, while inflammatory foods exacerbate tissue degeneration, increasing susceptibility to herniation.

Can Herniation Recur After Treatment?

Yes, herniation can recur after treatment. Despite various treatment methods, including surgery, recurrence is possible due to factors like inadequate post-surgery care, improper rehabilitation, or underlying conditions that predispose individuals to re-herniation.

What Are the Long-Term Effects of Untreated Herniation?

Untreated herniation can lead to nerve damage and chronic pain, potentially resulting in permanent disability. Continuous pressure on spinal nerves may cause sensory deficits, motor weakness, and further degeneration of affected intervertebral discs, necessitating advanced medical intervention.